What is Crimestat and how does it work – a brief history

On July 26th 2006 Council passed a resolution that directed the Administration to report back to Executive Policy Committee (EPC) and the Standing Committee on Protection and Community Services on the following:

What, if any, additional resources will be required to develop and implement a COMPSTAT style management and accountability mechanism that will provide weekly updates to citizens on crime trends on a geographical basis across each of the Police Districts; and, propose how the existing Police Command structure with its specialized operational units can be augmented by weekly organizational and strategy meetings chaired by the Chief of Police to respond to crime and safety concerns across each geographical districts and coordinate Clean Sweep Task Force Operations; and

How the Administration proposes to measure Police Service outcomes related to crime prevention and enhancement of neighborhood safety.

This direction resulted in the preparation and submission of a report outlining a Neighborhood Safety and Crime Prevention initiative which became known as Crimestat.

The nuts and bolts of the Crimestat initiative are contained in a report from the Police Service to Standing Committee dated January 5th 2007 which can be accessed at:

http://www.winnipeg.ca/clkdmis/ViewDoc.asp?DocId=6830&SectionId=&InitUrl= (look under Reports at the top of the page and scroll down to #85)

For the casual observer, Crimestat is simply a website that displays crime statistics and crime maps. For police, it’s significance is far greater. Crimestat is a management and accountability strategy that directs police commanders to concentrate on emerging crime issues and trends in the area under their command. It forces them to track criminal activity in their area, identify emerging crime trends, develop effective tactics, and deploy resources quickly to deal with emerging trends in their early stages before they develop into a full blown crime spree. Lastly, there is follow-up and assessment by the executive. This is the accountability feature of the process that ensures everyone (commanders in particular) have their eyes ‘focused on the ball’, the ball being crime prevention and crime reduction.

When Crimestat was introduced in Winnipeg in 2007 many were convinced that it could be a useful tool to prevent crime, not in the traditional crime prevention sense in terms of programming, but rather in an operational sense. What is visible on the public side of the Crimestat site is less detailed than what is available on the police side. If one studies the numbers (on the police side), specific crime trends can be seen developing in specific areas of the city. These trends can be nipped in the bud so to speak, largely by identifying and arresting perpetrators. These preemptive arrests prevent the trend from continuing and reduce the amount of crime. It’s not the be all and end all but it is a valuable tool. Like any tool, though, in order for it to work effectively a few basic rules must be followed.

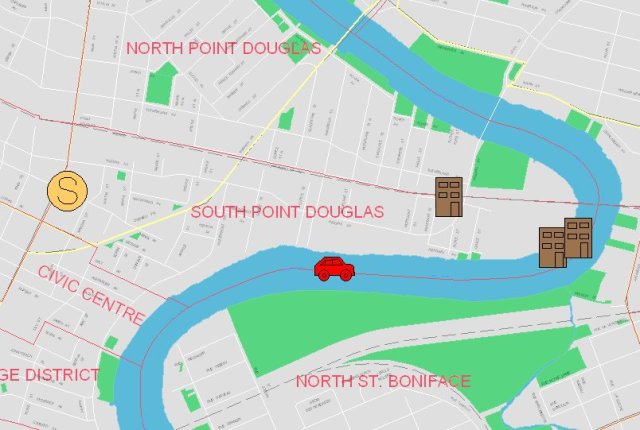

Here is an illustration of how it works: Using the neighbourhood of South Point Douglas as an example we can go back and have a look at the early stages of what looks to be a pattern of commercial break-ins.

Going back to July of 2009 (on the public site of the Crimestat site you can only go back one year) we see that during the months of July there were 3 break-ins in South Point Douglas.

For the sake of this exercise we will make that the starting point of a ‘trend’.

Source: Winnipeg Police Crimestat website

August 2009 (3 break-ins)

Source: Winnipeg Police Crimestat website

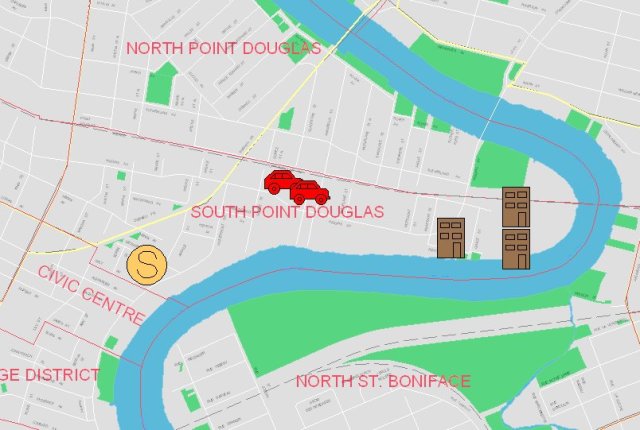

September 2009 (6 break-ins)

Source: Winnipeg Police Crimestat website

This trend continued with 0 in October, 3 in November, 1 in December, 3 in January, 0 in February, 4 in March, 2 in April and 5 in May.

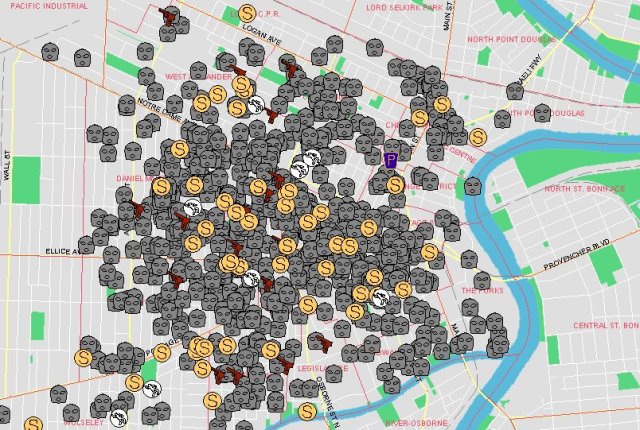

At the end of almost a year the crime map for South Point Douglas looks like this:

July 1st 2009 to May 30th 2010

Source: Winnipeg Police Crimestat website

During that 11 month period there were 30 commercial break-ins in the South Point Douglas neighbourhood.

Police Commanders are provided with this information virtually in real time. As a trend such as this one develops, commanders assign resources and tactics are developed. That is, if the series of events is recognized as a trend. Because there is a high likelihood that these 30 break-ins in close proximity to each other were not committed by 30 different perpetrators but rather by 1 or a group of individuals known to each other, the trend can be halted by identifying and arresting that individual or group of individuals.

Had that been done back in July of 2009 when the first break-ins in South Point Douglas occurred the next 30 could perhaps have been prevented.

That is a simplistic example of how division commanders can use Crimestat to prevent crime. The principle can be applied to other crimes at the community level.

Crimestat was designed to be a tool to track crime in our city’s neighbourhoods. It does that very well. The process has a proven record in helping to combat crime throughout major cities in North America. In order for it to be effective the tool must be used in the manner it was designed to be used. All players in the system must understand and execute their roles. Division Commanders must stay on top of crime in their area, identify trends and devise effective tactics to deal with them. The Police Executive must be fully engaged and ensure the resource is used as intended.

The executive of the Winnipeg Police Service does not appear to understand or appreciate the capabilities of Crimestat and that could explain why they have largely turned their backs on it. A key aspect of the Crimestat process centers on accountability. The Executive needs to hold Division Commanders accountable. Accountability is exercised most visibly during Crimestat meetings. That cannot happen if the Executive does not attend Crimestat meetings. Residents of Winnipeg have a vested interest in the overall safety of all neighbourhoods.

Winnipeggers need Crimestat to work.