While the crime rate (for the crimes types reported on Crimestat) in north Winnipeg (police District 3) is basically static a study of specific north end neighbourhoods shows a much different picture. Crime in neighbourhoods in close proximity to William Whyte is showing a disturbing trend. The crime rate in these high crime neighbourhoods is rising, in some case dramatically.

The recent multiple shootings in the north end have again focused attention on this part of the city. It is unfortunate that the only time these high crime neighbourhoods get attention is in times of tragedy.

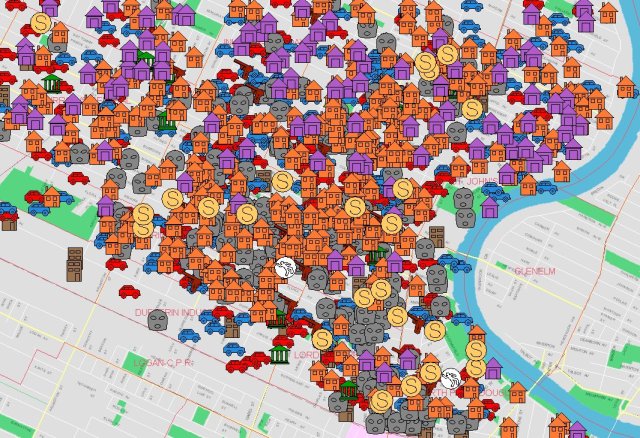

The map below depicts the crimes tracked on Crimestat for the south-east portion of District 3.

Source: Winnipeg Police Crimestat

The crime rate in these neighbourhoods is such that the icons depicting the various crimes overlap each other and it is difficult to appreciate the severity of the problem. For the sake of clarity one needs to eliminate some of the crime types. The image below illustrates the violent crimes (murder, shootings, robberies and sexual assault) for the area in question.

Source: Winnipeg Police Crimestat

A further examination of the crime trend in seven specific north end neighbourhoods shows the following increases:

| Neighbourhood | 2010 Year to Date | October 2009 toOctober 2010 |

| William Whyte | 1% | 5% |

| Dufferin | 11% | 18% |

| Burrows Central | 15% | 13% |

| Robertson | 25% | 25% |

| Inkster-Farady | 38% | 30% |

| St. John’s | 23% | 26% |

| Luxton | 16% | 32% |

Source: Winnipeg Police Crimestat

The important issue with these data is not so much the actual increase but rather the trend they represent. Increased crime in high crime neighbourhood or a cluster of neighbourhoods clearly demonstrates the area is not-self sustaining and needs help. The approach currently employed in these neighbourhoods is not working

The north end communities clustered around the William Whyte have received sporadic attention over the past couple of years usually related to tragedies such as shootings and homicides. When tragedies occur everyone (the police, the mayor and other civic and provincial politicians and the media) expresses outrage and vows are made to leave no stone unturned to bring the killer(s) to justice. As indicated in a previous post the police flood the area with additional personnel and the hunt is on.

Such a sudden influx of police resources is in and of itself not a bad strategy, in the short-term. It becomes problematic when it is the only strategy. Flooding high crime neighbourhoods with additional police resources drawn from other areas (operational and geographic) is not a sustainable strategy nor is it a strategy that addresses the long-term needs of the neighbourhood and its residents.

Earlier this year police resources were shifted from the north end (and other parts of the city) to the west end to deal with shootings there. Now resources are being shifted away from the west end back to the north end. This endless cycle of shifting resources to deal with emergency situations that crop up is symptomatic of a poorly planned (or unplanned ad hoc and reactive) approach to dealing with crime in high crime neighbourhoods.

The secondary flaw in the constant shifting of resources strategy is its reliance on using a strict law enforcement approach to address a much broader social issue. You may be able to apply a strict law enforcement approach and arrest you way out of a purely law enforcement issue but you cannot arrest your way out of a social issue.

The problem is that many tradition bound police executives are tethered to the strict law enforcement approach. They are not adequately familiar with cutting edge approaches to neighbourhood redevelopment and neighbourhood capacity building. Many don’t see that as a policing function. It may not be a policing function in the strict sense of the word, but what neighbourhood capacity building does is it empowers people and helps prevent crime. Based on the policing principles laid down by Sir Robert Peel (which in my view are still very applicable today) the prime mandate of the police is crime prevention.

The important issue is not how you strengthen neighbourhoods and reduce and prevent crime but rather that you do it. For high crime neighbourhoods in Winnipeg if that means the police need to go down ‘the road less travelled’, then let the journey begin.

The nature of the issue (problem) must dictate the approach. As well the nature of the issue must determine the timeline. Complicated social issues cannot be resolved using simplistic short-term strategies and tactics.

The question is this: is the Winnipeg Police Service willing to make the leap from using a traditional short-term reactive law enforcement approach to dealing with issues in high crime neighbourhoods to using a long-term proactive approach?

The Service certainly has the tools, the personnel and the budget to make it happen. The question is: do they have the will?